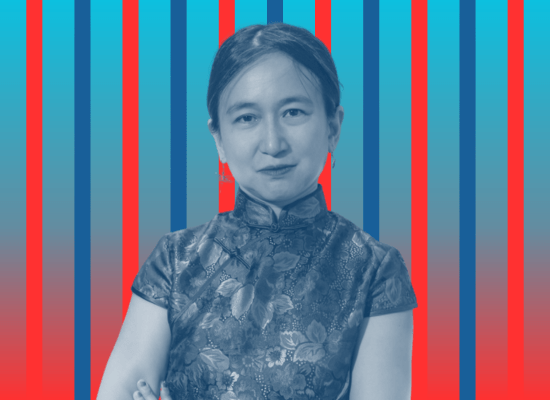

Victoria Law is a freelance journalist and author who covers incarceration. Her books include Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, Prison By Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms (co-authored with Maya Schenwar), and “Prisons Make Us Safer” and 20 Other Myths about Mass Incarceration. Her latest book, Corridors of Contagion: How the Pandemic Exposed the Cruelties of Incarceration, comes out in September on Haymarket Books.

Anthony Watkins:

Your book “Prisons Make Us Safer And 20 Other Myths About Mass Incarceration”, Beacon Press (April 6, 2021), does an excellent job of laying out the myths of our criminal legal system, as you call it. Whether someone is a law and order conservative or a reformist liberal, I think you offer eye-opening insights to myths held dear by both those on the left and the right.

I, for one, was surprised to realize how small both the non-violent offenders (14%) are compared to the overall prison population. I was also shocked to realize the private prisons, while still grossly offensive to my sensibilities are not the problem as only about 8% of the people incarcerated are in private facilities.

You make the case that prison labor neither drives mass incarceration, nor is it inherently bad for the people inside. The racial bias from policing to representation, to sentencing to treatment once inside is not surprising when you look at the overall racism of America, and the west, more broadly.

You talk of two alternative forms of justice that hold promise, both restorative justice, which reminds me a bit of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation process, and transformative justice that looks to do more than take the offender back to the state they were in before they committed their crime.

Both of these seem to be predicated on the offender to be willing to try to improve themselves and make amends.

Currently, most estimates show that it costs about $50,000 per year to maintain the imprisonment of an individual on average nationally, and maybe another $100,000 to place them there, in policing, and courts, etc. Can we transform our current legal system to a system of Restorative and/or Transformative Justice in a way that is more

effective and costs the taxpayer less money?

Victoria Law:

We most certainly can move away from our nation’s current system of punishment and imprisonment, but we need to have the political willpower to do so.

Our current legal and carceral systems are not only expensive, but also highly ineffective. The legal system is adversarial, meaning that a person facing incarceration has no incentive to admit to, let alone reflect upon, the harm that they’ve caused. Instead, they are encouraged to deny all culpability, minimize the damage they’ve wrought, and, in many cases, steer blame back onto the victim(s).

If they are convicted, little in the prison system encourages a person to take responsibility and reflect on their actions. Few programs or other opportunities push them to improve themselves—and the few that exist often have long waiting lists. In many prisons, the people who are serving the longest sentences are last in line to get into the few programs that may allow them to transform themselves. Instead, they are essentially warehoused with little to no opportunities that encourage reflection or positive change. Throughout the years, I’ve interviewed people who have gone in and out of prisons and, over and over, they’ve talked about how their early prison terms didn’t offer anything that encouraged them to rethink their mindsets or priorities.

Sometimes, prisons offer programs which turn out to be obsolete and useless—which they didn’t learn until they were released from prison and attempted to use these newly learned skills. That’s what happened to Jack, a trans man who has been in and out of Texas prisons. In 2001, he enrolled in the prison’s computer maintenance course. He was excited about learning a skill that would be in great demand—and even convinced his parents, who were living on an extremely fixed income, to pay the $100 needed for his certification test. When he was released the following year, he was crushed to learn that those skills were long outdated. This is a story I hear again and again from people inside—that even when they try to improve themselves or their outcomes, what they learn inside are inadequate for outside jobs.

Remember too that our current carceral system, as pricey as it is, does little for those who have been harmed—whether directly or indirectly.

Restorative justice centers the needs of the survivor(s) rather than simply seeking to punish the person who caused harm. The process also includes people who have been indirectly affected, such as family members and other loved ones. This typically involves a facilitated meeting in which survivors are able to talk about the long-lasting effects of the harm caused and what they need to begin healing, including actions the harm-doer(s) can take. The person who has caused the harm is encouraged to take responsibility for their actions and work to repair the devastation they’ve caused.

Transformative justice centers the needs of the survivor while also working to transform the conditions that enabled the harm. In other words, it approaches what happened not as an individual action or set of actions, but also seeks to identify and address the context in which it occurred.

Neither of these are quick fix solutions. These processes can take months, and sometimes years. But, unlike our current system, they actually address root causes of why harm occurred in the first place and what can be done for both those who caused the harm and those who were hurt by it. Research in the U.S., Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom have all shown that restorative justice can help break the cycle of violence and reduce recidivism by as much as 44 percent. Compare that to the U.S. Department of Justice analysis that found that 82 percent of people released from state prisons were rearrested at least once in decade after their release.

Anthony Watkins:

Assuming both Restorative and Transformative Justice could be put into practice on a wide scale, assuming we put physical health, mental health, education, and economic opportunity as priorities BEFORE crimes are committed in “at risk” communities, instead of taking the over-policing approach we currently use on poor, black, brown, LGBTQ,

and otherwise marginalized communities, with more social network support, could we end ALL crime?

Victoria Law:

First, let’s separate the notion of “crime” from “harm” or “damage.” Crime is a legal construct that makes one type of action illegal (and punishable by imprisonment or other restrictions on liberty, like house arrest, electronic monitoring or probation). The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that homelessness can be classified as a crime. But homelessness is actually a failure of our shredded social safety net.

Additionally, not every harmful act is considered a crime punishable by the legal system. Homelessness can now be classified as a crime. But rarely do we consider these as crimes—even though they cause homelessness: speculating on real estate, charging rents that are increasingly beyond reach, neglecting or withholding necessary repairs to homes, or warehousing (or deliberately keeping empty) apartments that are rent-stabilized or legally mandated to be below the exorbitant market rates while thousands are sleeping on the streets.

But to get to the crux of your question: If we prioritized pouring more resources into physical and mental health, education, economic opportunities, housing, food, and all of the other needs that people have—and if we addressed harm with practices like restorative and transformative justice rather than tossing people into cages for a certain period of time, we would live in a much safer society. Would it stop greedy restauranteers from stealing tips and wages from their workers? Maybe not. But having more resources, such as greater economic opportunities and more affordable housing (and food), might enable workers to not continue laboring for an exploitative and thieving boss in the hopes that they might eventually get some of that back pay.

Would focusing more on restorative and transformative justice end all harm? No. There would still be interpersonal conflict—which could lead to harm. That would still need to be addressed. But if there were more abundant resources—in ways that we see wealthier (and often whiter) enclaves enjoy–we wouldn’t see the kind of widespread devastation currently present in so many poor and marginalized communities.

Remember, the United States has the world’s highest incarceration rate. Many of our country’s individual states have higher incarceration rates than other nations. If incarceration actually kept us safe, the U.S. would be the safest country in the world. But that’s not the case—yet this country continues to pour billions into a system which has continually failed.

Anthony Watkins:

If not, what would we do with the ones who rape and rob and murder in spite of the utopian try to we create?

Victoria Law:

We have to remember that our current system doesn’t work to prevent violence and harm. It only comes into effect after a crime has been committed.

Our current system doesn’t do much to address physical harm like rape and murder even after it happens.

In addition, the federal government’s own survey found that two of every five instances of non-fatal violence are not reported to police at all. When it comes to rape and sexual assaults, the percentage of people who turn to the current policing and legal system dwindles even further—one study found that, of every 1,000 rapes that occur, only 310 (or less than one-third) are reported to the police. From there the numbers dwindle even more: Of those 310 rapes that get reported, only 50 lead to an arrest. Of those 50 arrests, only 25 result in a conviction.

Similarly, one-third of murders remain unsolved. But even those classified as “solved” doesn’t mean that the person who has taken someone else’s life is in prison or otherwise being held responsible for their actions. It simply means that police have identified who might have done it—but that person might have died, or simply not been convicted.

At the same time, community members and communities are organizing efforts around safety and harm. Some groups are finding solutions to the question, What does safety look like when you are in a community where people are homophobic and transphobic but you are also likely to face homophobic and transphobic violence from the police as well? What do you do when someone’s been sexually assaulted? One Million Experiments, the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, and Creative Interventions are all examples of efforts to help communities address sexual violence without depending on the police.

There’s not a one-size-fits-all model. The neighborhood model in Crown Heights, a largely Afro-Caribbean community in Brooklyn, likely won’t be the same as what works for Seattle massage parlor workers facing both client, police and anti-Asian violence and those would look very different than mothers organizing against street killings in Chicago.

Anthony Watkins:

Your book makes it clear that what we are doing now is not to the benefit of the wider population, not to mention the human beings we lock away and tend to forget about.

If prisons do not keep us safe, if prison labor doesn’t provide the main incentive to grow the prison population, if private prisons making a profit are not the driving force behind the mass incarceration explosion, why do we still have the mass incarceration?

Victoria Law:

Even though prisons don’t keep us safe, prison labor is oftentimes a money loser, and private prisons lock up eight percent of the total state and federal prison population (although they confine the vast majority of people in immigrant detention), we—as a nation—continue to buy the myth that, without incarceration, we would descend into chaos and violence.

We see this myth reinforced nearly everywhere—on the nightly news, which trumpets crime and destruction; on TV shows and movies which valorize police, even when they are portrayed as bumbling comedians; and in so much of the media we consume. It’s hard—though not impossible—to push back on generations of conditioning.

Anthony Watkins:

Who is making the money off of the current system?

Victoria Law:

While profit is not the main motivation behind mass incarceration, we have to remember that there are still corporations—many of them—that are parasitical profiteers from the United States’ addiction to imprisonment.

This includes prison telecommunications corporations—or companies that specifically were formed to profit off incarcerated people’s desires to stay in touch with their loved ones. State prison systems and local jails contract with one (or more) of these corporations to provide phone services and, increasingly, electronic messaging (or a very glitch e-mail system that does not connect to the wider internet and is continually monitored and censored) and video visitation. Each of these services comes at a cost—typically to the incarcerated person and/or their loved ones. In more than 40 states, phone calls cost 6 cents or more per minute. Some families spend hundreds of dollars each month to stay in touch with their incarcerated loved ones.

Electronic messaging can cost up to 43 cents per message. If a family member wants to send photographs with their message, each photograph costs an additional “stamp” and those costs can add up to much more than the cost of printing out photos at the drug store and stuffing them into an envelope. And sometimes the interface sends the same message multiple times, charging the user a “stamp” for each time. (This happened to me earlier this summer and today, when I briefly stopped answering questions to answer a prison e-message! Good-bye 43 cents x 4!)

Finally, jails are increasingly using them to replace in-person visits. We saw this even before the pandemic stopped all in-person visiting, jails had been increasingly replacing in-person visits. And those video visits also cost money.

That’s only one way in which private firms profit from incarcerated people’s needs. We also see companies that have been set up explicitly for medical care (or, more often, lack of care), transportation, and other prison necessities. These corporations don’t provide these same services to people not in prison—they exist solely because incarceration exists.

Worth Rises, a non-profit that tracks companies profiting from mass incarceration, has identified over 4,100 private companies that currently do so. They range from architects and engineers who build and expand carceral facilities to furniture makers, from food services to IT and other records keeping.

But it’s important to remember that these corporations are not driving forces of incarceration. Instead, they are the parasites that are feeding—and siphoning off public money that could instead be used to fund resources that would actually address harm and violence, or even prevent them from happening in the first place.

Anthony Watkins:

Is there another motive for mass incarceration besides profit?

Victoria Law:

Yes. As Angela Davis has pointed out, incarceration serves to disappear social problems. Instead of addressing societal problems such as poverty, homelessness, gender violence, homophobia and transphobia, racism, and other ills, incarceration removes the people who are most vulnerable to them from public view. This doesn’t solve any of these problems, which continue to exist. Instead, incarceration serves as a magician’s disappearing act.

The U.S. has long used incarceration to remove people or populations that are considered undesirable from public view. We’ve seen this with the arrest and removal of Native and indigenous people during the “settling” of the Midwest and the American West. After the Civil War, southern states passed Black Codes designed to criminalize newly-freed Black people. Under the Black Codes, they could be arrested for a wide range of behaviors, such as being outside after a certain hour, gathering in small groups, being absent from work, vagrancy, or possessing a firearm. People arrested under the Black Codes were forced to do backbreaking labor for free—either for the county or for private companies, which leased them. This might lead to the idea that profit was the main motivation for incarceration. However, the Black Codes did not extend to white people, who could—and did—engage in these actions without being arrested or forced into labor.

We also have to remember that incarceration is expensive. Grants Pass, Oregon, which criminalized homelessness, is a prime example. Oregon spends $109 per day (or $3,379 per month) to keep a person in jail. The average studio apartment in Grants Pass costs $925 per month. With incarceration, the police and the local government can make the homelessness problem seem to disappear—while actually not addressing homelessness. And city decision makers would rather spend more than three times as much on this non-solution than an actual solution.

Anthony Watkins:

You make the case that prisons are AFTER-THE-ACT and don’t prevent crime and harm done, but I think most people say even if the “bad guy” does murder someone, by locking him up for 25 years, that is 25 years he cannot murder anyone else on the outside (and honestly, I think most average Americans don’t care if one person in prison kills another person in prison).

Obviously, if we have a system that prevents crime in the first place, that is better. Can we tell the average American, who have shown little interest the plight of those who are locked up, that we can make them safer for less money?

Victoria Law:

Yes, we definitely can. As you pointed out with the first question, incarceration is expensive. Not only is it not cost-effective, but it also doesn’t work to either prevent or address the harm that’s caused.

We also have to remember that the vast majority of people in prison are released and come home. For the “average American” who doesn’t care about those who are in prison, we should ask: do you want to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars warehousing people who will come home even more damaged—and be more likely to lash out and hurt someone(s), which might be you or someone you love? Or do you want to live in a safer society?

Most people want safety. They don’t want to live in a Mad Max world. We’ve been fed the myth that, without the threat of imprisonment, we would end up in that kind of dystopian, chaotic and destructive world.

It’s worth repeating that the U.S. has the globe’s highest incarceration rate. If incarceration kept us safer—we would have long been the world’s safest nation. But that’s not the reality here in the United States—or in many other countries that have followed the U.S. model of increasing criminalization and incarceration to hide the people who have most been failed by prioritizing cages over care.

Anthony Watkins:

As always, when I interview, I ask the subject of the interview to answer the question or questions I failed to ask. What did I miss?

Victoria Law:

The COVID-19 pandemic was a missed opportunity to rethink the nation’s addiction to incarceration. To stem the spread of a highly-contagious and lethal disease, other countries—including Iran, which is not known for its adherence to human rights—released tens of thousands of people from its prisons. Some states and local jurisdictions released some dozens or hundreds of people a few months earlier, but these were not enough. Early on, eight out of ten COVID hotspots happened in jails and prisons.

Instead, what we saw was a doubling down of punitive measures, such as locking people in their cells for nearly 24 hours each day and, when visiting resumed, forbidding people from touching one another, under the guise of public health and care. These punitive measures continued long after the U.S. declared the pandemic emergency over—and are emblematic of the ways in which carceral logic distorts protection into even greater punishment.

But just because we missed that opportunity in 2020 (and in 2021, 2022, 2023 and this year) doesn’t mean that we can’t shift courses now. We can still think about what we, as a society not just as individual people or neighborhoods, need to ensure widespread safety, including the safety of those who often fall through the cracks. And then we can work to challenge the misguided priorities of policing and prisons and work towards building and funding the resources needed to ensure that everyone can not only survive, but thrive.

Leave a comment